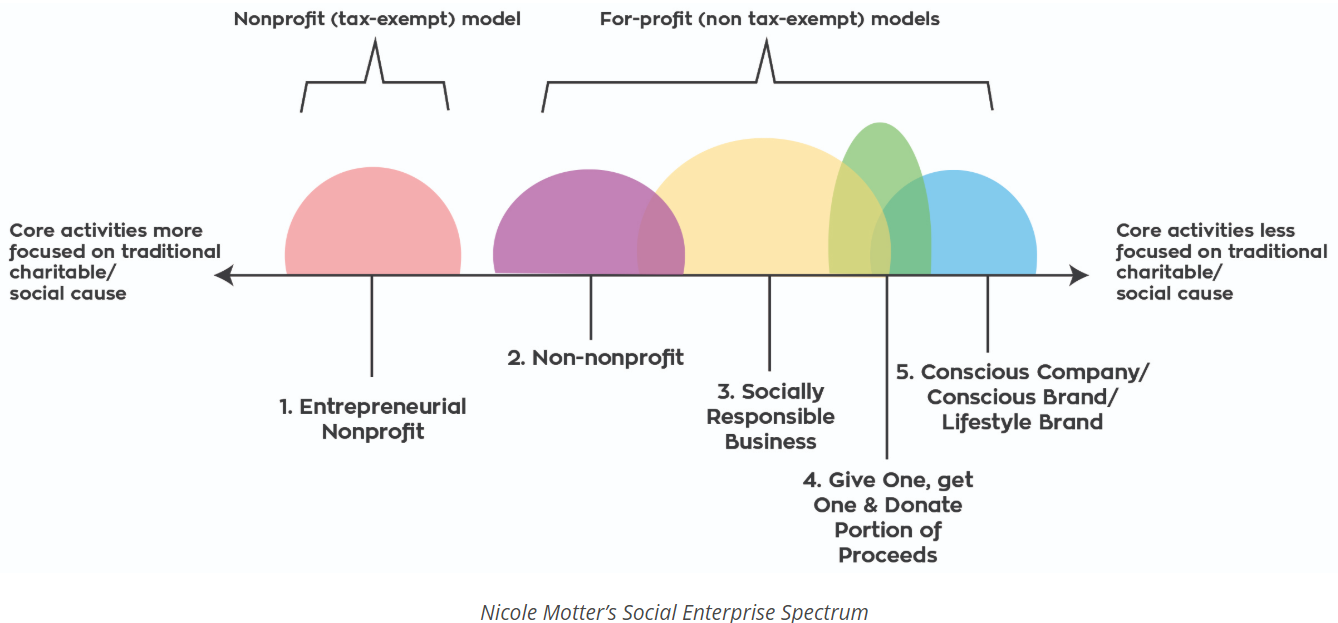

The term “social enterprise” can mean a lot of different things. Where on the spectrum does your favorite one fall?

“What exactly is a social enterprise?” It’s a question that comes up a lot, probably because there isn’t a consensus. Generally speaking, “social enterprise” means using business tools to address a social need. This concept may or may not overlap with “social innovation” which means addressing a social need in a new, groundbreaking way. While it’s possible to use business tools without using them innovatively, and it’s possible to innovate without using business tools, the posterchild for this sector works at the intersection of these two concepts.

Yet for most people, “social enterprise” winds up being the broad, default phrase used to cover both concepts. For better or worse, that expansiveness has snowballed the term’s popularity (the bigger the bucket, the more stuff you can throw in there), but has also led to trouble agreeing on a definition. The various “social enterprise” definitions can include some or all of a number of models: small nonprofits using entrepreneurial practices on one end of the spectrum; big, mainstream companies using environmentally sound practices, treating their employees particularly well, and/or donating a portion of their proceeds to pre-existing charities on the other. In the middle you’ll find other definitions, with plenty of debate over what belongs, including the degree to which an entity’s primary activities must tie to its a social mission, the necessity of including social commitment in an entity’s formational documents, and whether a side-project of an existing organization should count as a “social enterprise.” Meanwhile, some definitions provide for overlap. Bottom line: it’s confusing.

As a social enterprise consultant and lawyer, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to think about how to make sense of the various organizations we sometimes call “social enterprises.” Here’s how I categorize the spectrum.

1. Entrepreneurial Nonprofit

These are tax-exempt entities supported, at least in part, by earned income (although I’ve seen it argued once or twice that an innovative nonprofit idea, even without earned income, makes the cut). To reach entrepreneurial nonprofit status, these organizations can either (a) implement a revenue-generating program, or (b) adopt an overall entrepreneurial business model.

Funding

Their main funding source is typically grants from foundations and donations from the general public (the cornerstone of the tax-exempt nonprofit model), although in some circumstances loans from banks, or from foundations in the form of program-related investments, are also possible.

Examples

(a) Girl Scouts of America, with their much-loved cookie sale program; (b) Daily Table and With Love L.A., retail grocers bringing healthy, affordable food options to neighborhoods that don’t otherwise have access.

2. Non-nonprofit

Never heard of this one? I’m not surprised — I made it up, for the sake of clarifying often-overlooked yet meaningful distinctions. These organizations start with social mission, much like a nonprofit, and then figure out a way to make it work outside the restrictions of a tax-exempt model — in other words, they’re a for-profit business. They exist primarily to address a social issue (“mission-first” or “mission-centric”), with revenue-generating activities intertwined with change-making activities.

They don’t form as for-profits because they are in business “for profit”; rather, it’s a decision that allows for higher-capacity growth, sustainability, innovation, and risk-taking — all components of highly successful entities in other sectors — than is generally permitted under the regulations that come with tax-exemption.

Funding

The ideal funding source here is program-related investments from foundations, which provide low-cost capital at a critical early stage and prevent compromising the fullest expression of mission for financial returns down the road. In some cases, grants from foundations or investments from traditional angel investors or venture capital firms may also be possible.

Examples

Everytable, seeking to eliminate food deserts through affordable grab-and-go meals with a first-of-its-kind sliding scale model; and InvestED, opening access to capital to low-income entrepreneurs globally with a creative combination of edtech and fintech. Others that fall in this category include Generation Genius, Amplio Recruiting, Nightingale Apps, Tickleberry Place, Mini City, Neopenda, and Drinkably.

3. Socially Responsible Business

This is the biggest bucket of them all, and includes benefit corporations, B Corps, and all things double- and triple-bottom-line. While these types of entities can be created primarily to address a social issue, it’s more common that this categorical distinction is based on the adoption of practices benefiting community, employees, or environment (generally more aligned with the idea of doing business better than solving social problems). In the case of benefit corporations and B Corps, this distinction is included in the company’s formational documents, along with a provision stating that they are legally permitted to honor this distinction (whether that be company culture, responsible sourcing, etc.), even at the expense of shareholder profit maximization.

Worth noting here is that benefit corporations are a legal entity formed at the state level, whereas B Corp is a certification available to other for-profit entities (such as corporations and LLCs). Double-bottom-line denotes a focus on social returns alongside financial ones, while triple-bottom-line denotes a focus on environmental, social, and financial returns.

Funding

Primary funding options here include traditional angel investments and venture capital, as well as program-related investments in some circumstances.

Examples

THRIVE Farmers Coffee, on the more mission-centric side; Ben & Jerry’s and Patagonia, on the more build-a-better-business side.

4. Give One, Get One / Donate Portion of Proceeds model

These are companies that direct some portion of their business toward charitable work, and are almost always layered into the preceding and subsequent categories (falling on either side of it in the diagram above). Revenue-generating activities are generally wholly separate from change-making activities and, in many cases, the social component is an add-on to the company’s core business. Because these models generally feed back into traditional nonprofit system, I break it out as a separate subcategory.

Funding

Same as above

Examples

TOMS, Warby Parker, Good Spread, Newman’s Own.

5. Awareness Brand

While some will expand these terms to include virtually everything in the previous two categories, we think they also capture a different type of company not yet mentioned — those that sell products designed to engage community and bring awareness to a social issue, but whose primary activities don’t necessarily address the root cause of the social problem they’re bringing awareness to.

Funding

Same as above

Examples

Beautiful in Every Shade, So Worth Loving.

6. Everything else

There is no one size fits all, and not every entity will fit neatly in these categories (particularly given the constantly evolving nature of this sector). The social enterprise employment model, which uses the business to provide meaningful work and empowerment to a disadvantaged population (like Bitty and Beau’s Coffee), is a component that can be layered into any of the categories discussed above

Then there’s outliers like Fruitcraft (formerly the California Fruit Wine Company), which is pioneering an entirely new model they call social value enterprise (SVE). While an untrained eye might classify this as a socially responsible business (group 3 above), the folks behind Fruitcraft are very clear about striving for more — namely using market forces to incentivize and reward thinking about the whole — with three defining aspects they claim put SVE in a category of its own:

- democratic ownership by employees, (including accountability and decision making within the company)

- no possibility of sale (keeping the company permanently stewarded by the workforce for the benefit of society)

- unleashing 100% of profits for social good

Don’t get caught up in the labels

While there are a lot of options out there, at the end of the day, the label doesn’t really matter, except for those that have tax and legal considerations (talk to a professional about those). What matters is that you’re creating something meaningful — whatever model or business idea you’re considering, whether it’s one on this list, or something else altogether. The moral of the story: If you feel a tug from deep inside to do something good, just do. I bet you’ll wind up creating something beautiful and adding social value in a way that only you can.

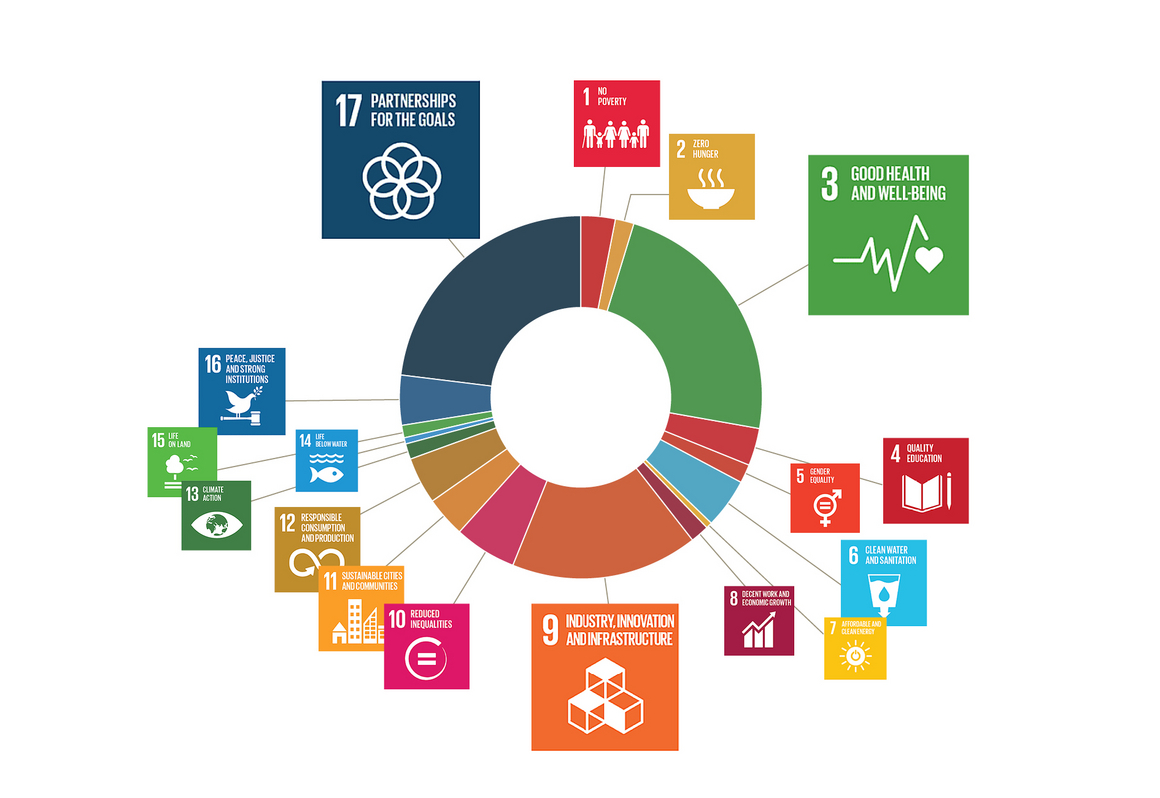

#socialenterprise #socialfinance #mba #wbs #toronto #ontario #consulting #sdgs #sustainability #ESG #impactinvesting #venturecapital #privateequity #thesectorinc #bradfordturner #peace #love #change #socialentrepreneurship