A social enterprise is an activity of a nonprofit that employs entrepreneurial, market-driven strategies for earned income in support of its mission. This outline for a social enterprise business plan is a guide for research, planning, and writing a business plan for nonprofit social enterprises.

A social enterprise is an activity of a nonprofit that employs entrepreneurial, market-driven strategies for earned income in support of their mission. Business plans are a common tool for entrepreneurs when starting or growing a business enterprise. For nonprofits that are starting or growing a social enterprise as a part of their program activities, developing a business plan is an essential step. While social enterprise business plans address all of the questions needed for any business, nonprofits also need to consider the alignment with mission, organizational background and structure, and evaluation of both financial and social impact.

This outline for a business plan is a guide for research, planning, and writing a business plan for nonprofit social enterprises. The sections below are provided as a roadmap for the plan. Most business plans include each of these sections, though the length and amount of detail will vary depending on the nature of the enterprise, the complexity of the organization, and the purpose and audience for the plan.

Executive Summary

The Executive Summary provides the most important information for readers that need to understand and support the concept but not necessarily know the detailed plans. This is usually written last.

- Organizational description

- Business concept

- Market description

- Value proposition, or competitive advantage

- Key success factors

- Financial highlights and capital requirements

Mission

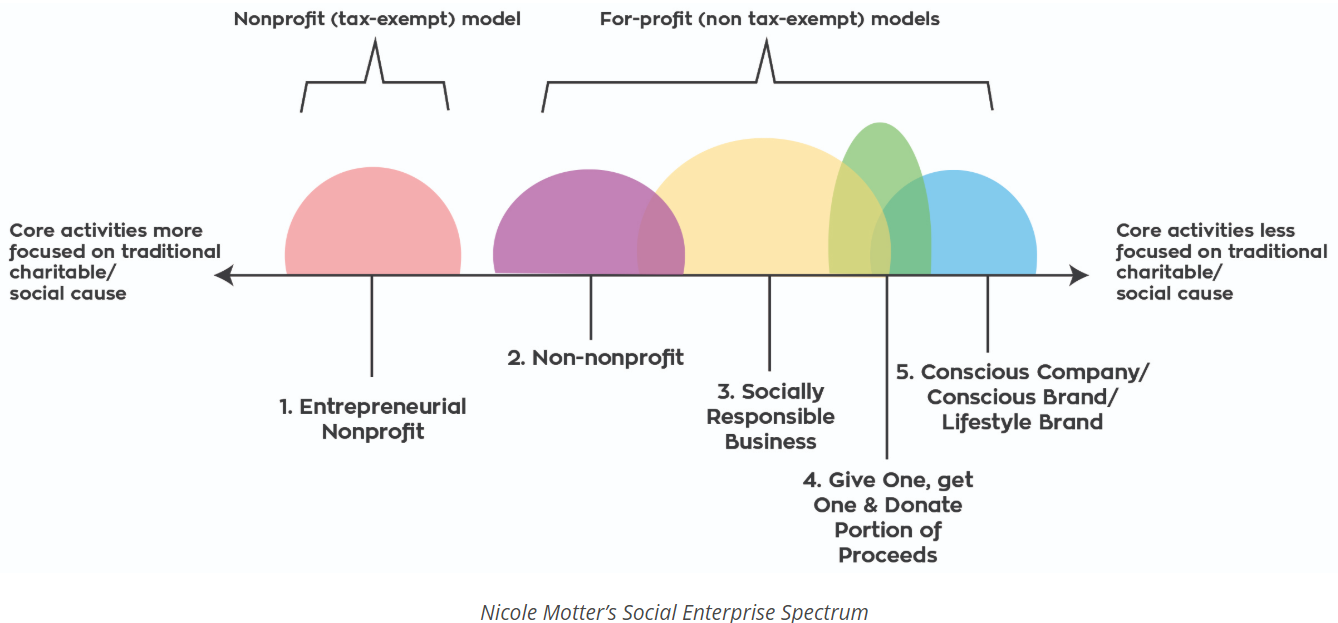

A social enterprise of a nonprofit organization may contribute directly to achieving mission; may be complementary or supportive of mission; or may be unrelated to mission (with primarily financial goals). The alignment to mission is a critical question.

- Organization mission and/or vision statement

- Relationship of social enterprise to organizational mission, or separate mission for the enterprise

Background and Structure

This section summarizes the organization’s history and programs and how the enterprise will fit in to the larger organization.

Most social enterprises operate as an activity or program within the nonprofit, though some are legally structured as a separate nonprofit, a for-profit subsidiary, or an independent organization.

Form should follow function and the legal structure should support the purpose and activities of the enterprise. Advice from an expert attorney may be needed.

- Brief description of the nonprofit, including context and programs

- How the business venture will be structured in the organization

- Legal structure and governance (Boards, advisory committees, reporting)

Market Analysis

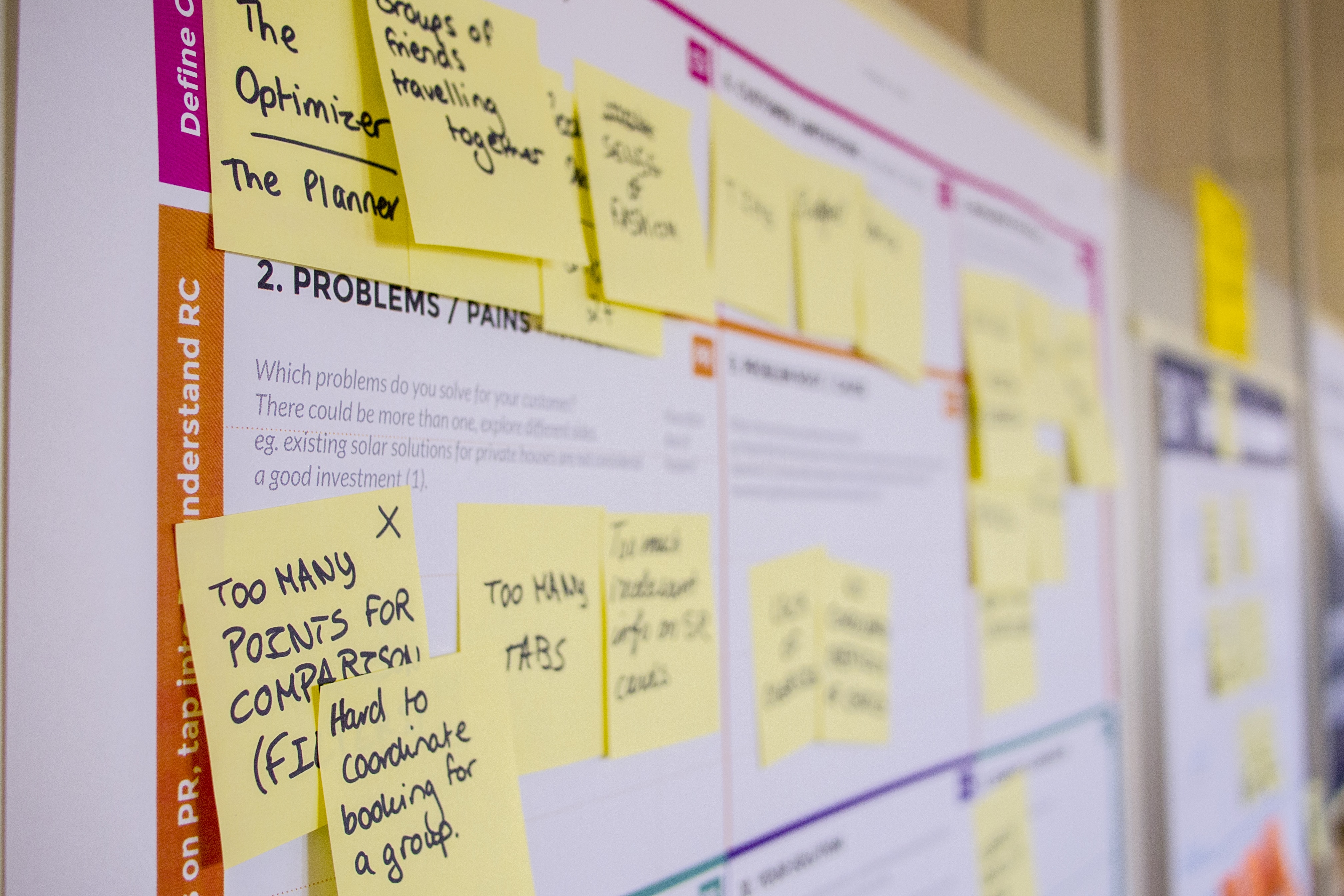

The market analysis is the heart of the business plan and is too often inadequately explored when planning a social enterprise. Solid research is necessary to understand the target customers and how the enterprise will meet a gap and demand in the market. No amount of mission or commitment will overcome a deficiency in market knowledge and a bona fide demand for the product or service.

- Summary of current market situation

- Target market and customers

- Customer characteristics, unmet demands and buying factors

Competitive Analysis

This section describes the competitors, both nonprofit and for-profit, and the value proposition, or market advantage, of the proposed business.

- Primary competitors

- Competitive products/services

- Risks and opportunities in competitive market

- Recent or emerging changes in the industry

- Specific description of competitive advantage/value of proposed product or service

Products/Services

This section is a summary of the product or service that will meet the demand in the market. It does not need to include detailed descriptions, price lists or other materials.

- Product/service description

- Positioning of products/services

- Future products/services

Marketing and Sales

This section will describe how the organization will reach the target market and turn those prospects into paying customer.

- Marketing strategy

- Sales tactics

- Advertising, public relation, and promotions

- Summary of sales forecasts

Operations

This is the “how to” section, describing the creation and delivery of the business’ product or service.

- Management structure

- Staffing plan and key personnel – if this includes programmatic elements related to the mission, expand this section

- Production plan or service delivery, including summary of costs of materials and production

- Customer service/support strategy and plan

- Facilities required, including specialized equipment or improvements. If the business is retail, discuss location characteristics

Evaluation and Assessment

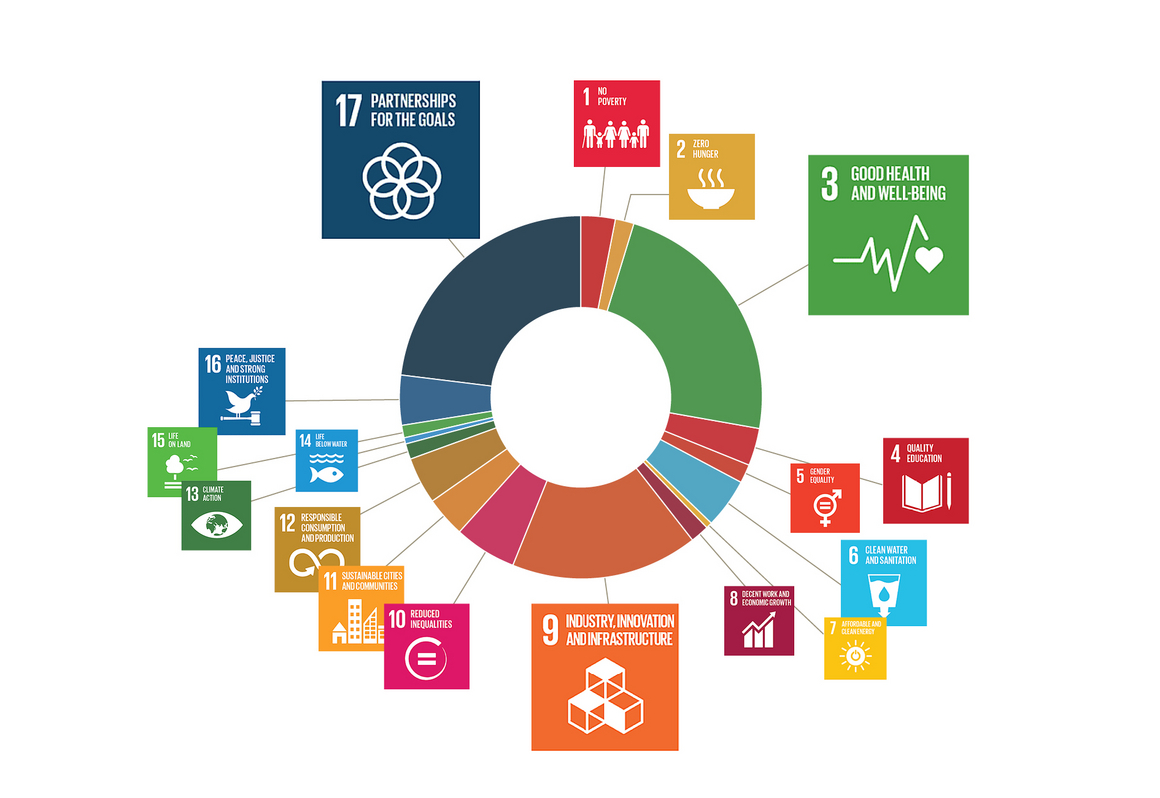

Most for-profit businesses measure their success by the financial results. Social enterprises have a double bottom line (or a triple bottom line.) This section describes the factors that will be evaluated to assess the success of each aspect of the enterprise.

- Quantifiable financial goals

- Quantifiable mission goals

- Monitoring and evaluation strategy

Financial Plan and Projections

The financial section includes projections for revenue and expenses for at least three years with a summary narrative of the key assumptions. This section also details the start up costs for capital equipment, inventory, initial marketing and staffing, and subsidy needed to cover losses during the start up period. These capital requirements may be funded from a combination of contribution from the nonprofit, grants for the enterprise, and/or debt financing.

- Start up costs and investments in equipment, technology, or one time costs

- Capital requirements and sources

- Income and expense projection

- Pro forma balance sheet for start up

- Cash flow summary or projection

- Assumptions and comments

Are you interested in planning a social enterprise? Get in touch: info@thesectorinc.ca

#socialenterprise #socialfinance #wbs #mba #consulting #thesectorinc #peace #change #impactinvesting #ESG #philanthropy #socialentrepreneurship #sdgs #socialinnovation #sustainability #bradfordturner